Gastric Dilation and Volvulus Syndrome

Written by: Riley Holman, 1st year Veterinary Student • 2019 Scholar

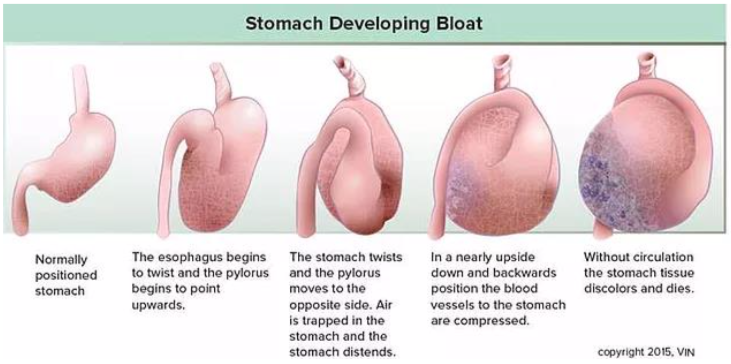

Blackwells’s Five-Minute Veterinary Consult defines gastric dilation and volvulus syndrome as a disease that occurs in dogs in which the stomach dilates and consequently rotates around its short axis. This syndrome is known by the acronym of GDV and also referred to as “Bloat” or “Gastric torsion”. GDV is an acute, life-threatening emergency. Volvulus is the twisting of a bloated stomach resulting in decreased blood flow to and from the stomach, which can eventually lead to shock.

Risk factors:

Although there is no direct genetic predisposition for GDV, dogs with a first-order relative with a history of GDV are at greater risk. Large and giant breeds have a reported incidence rate around 6%. The anatomical arrangement in deep-chested dogs serves as a predisposition to larger dogs and is strongly linked to activity/exercise after a meal. Low and high food bowls can encourage aerophagia, which also serves as a risk factor for GDV development. Speedy eaters and those with gastrointestinal neoplasia are at a greater risk as well. Other risk factors include dogs with a nervous/stressed temperament, feeding large volumes of food at each meal, and feeding foods high in fats/oils.

Pathophysiology:

- Exact mechanism of GDV is poorly understood and remains unknown.

- Volvulus can occur in any direction, but majority occur in clockwise rotation when the animal is in dorsal recumbency (laying on its back) and the surgeon is viewing patient from caudal view (from behind the animal).

- Contributing factors include: ingestion of a large amount of food or water, delayed gastric emptying, and excessive post-prandial activity.

- After the stomach rotates, gas (CO2) and fluid continue to become entrapped within the stomach and distention of the stomach is progressive.

- Progressive distention increases intra-abdominal pressure, which compresses major blood vessels: caudal vena cava, portal vein, and compliant blood vessels of the abdomen.

- Decreased cardiac return leads to hypovolemic shock (shock caused by a loss of blood volume).

- Decreased perfusion can cause systemic effects such as organ necrosis, local and systemic inflammatory cascades, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

Systems Affected:

- Gastrointestinal

- Decreased perfusion -> ischemic necrosis of the stomach (tissue death d/t decreased oxygen supply)

- Increased metabolic demand -> mucosal ischemia

- Cardiovascular

- Decreased venous return -> hypovolemic shock -> decreased cardiac output -> organ hypoxia -> tissue damage/death

- Decreased myocardial perfusion and increased inflammatory mediators -> arrhythmias (premature ventricular contractions)

- Respiratory

- Upperairwayobstructiond/tregurgitationandaspirationofexcesssalivaswallowed

- Decreased thoracic capacity-> hypoventilation (decreased oxygen exchange) and hypoxia

- Endocrine/metabolic

- Circulatoryshock->lacticacidosis

- Fluid translocation -> hypokalemia (decreased blood potassium levels)

- Hepatobiliary

- Liver compromised d/t venous congestion and shock -> bacteria cannot be removed via portal system-> septicemia

- Hemic/Lymphatic/Immune

- Splenic insult d/t avulsion of short gastric vessel, splenic torsion, or splenic infarction.

- Bacterial and endotoxin translocation into lymphatics and bloodstream d/t disabled GI mucosal barrier

Signalment:

Signalment:

- Large & giant breed dogs with large, deep chests

- Can occur at any age, but risk increases with age

History (Signs & Symptoms):

- Vomiting or non-productive retching or dry heaves

- Anxious, restless, agitated, reluctant to lie down

- Sudden collapse, lethargy

- Ptyalism (excessive salivation) and swallowing

Physical Exam:

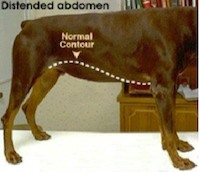

- Distended/large/rigid abdomen or stomach

- Abdominal pain and distension

- Tachycardia (fast heart rate)

- Tachypnea (fast respiratory rate) or dyspnea (difficulty breathing)

- Weak pulses

- Pale, tachy mucous membranes (dry gums) Prolonged capillary refill time (decreased blood perfusion to the

gums)

Differential Diagnosis:

- Acute pancreatitis, Gastroenteritis, Intestinal obstruction/ intussusception/neoplasia, colitis, obstipation, necrosis, rupture, ulceration, perforated GI tract, surgical wound dehiscence, mesenteric torsion, duodenocolic ligament entrapment, pancreatic abscess/neoplasia, dietary indiscretion (Thompson, pg. 160-161). Septic peritonitis, splenic torsion, abdominal organomegaly, Megaesophagus, esophageal foreign body, and hemoabdomen/abdominal effusion need to be ruled out as well (Mazzaferro, pgs 245-246).

Diagnostics:

- “Food bloat” is the common name for gastric dilation without concurrent volvulus.

- Ventricular dysrhythmias can be seen pre-, intra-, and post-operatively.

- CBC- stress leukogram, hemoconcentration, thrombocytopenia, anemia

- Biochemistry- electrolyte abnormalities common

- Sometimes azotemia d/t hypovolemia

- Urinalysis- can see increased specific gravity d/t dehydration

- Plasma lactate concentration- usually increased, can predict gastric necrosis and prognosis.

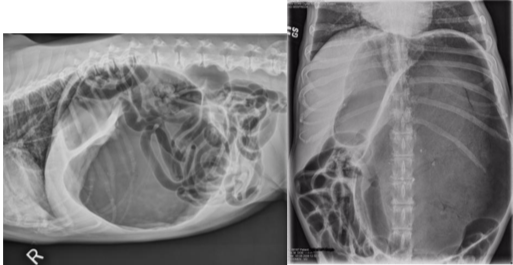

- Radiograph/X-rays (once patient is stabilized)-right lateral abdominal-> reveals pathognomonic compartmentalization of stomach (presence of dilation and/or volvulus).

- Dorsal ventral view- may help confirm the disease

Treatment:

Urgent hospitalization, thorough examination, and immediate cardiovascular support are all necessary for patient to survive. Depending on patient’s situation, crystalloid or colloid fluids may be used for therapy or a combination of both to treat the shock. Crystalloid therapy would be a dose of 90 ml/kg of isotonic solution dispersed over 30-60 minutes via cephalic or jugular vein.

Urgent hospitalization, thorough examination, and immediate cardiovascular support are all necessary for patient to survive. Depending on patient’s situation, crystalloid or colloid fluids may be used for therapy or a combination of both to treat the shock. Crystalloid therapy would be a dose of 90 ml/kg of isotonic solution dispersed over 30-60 minutes via cephalic or jugular vein.

Once patient is cardiovascularly stable, gastric decompression should be performed immediately. This can be done by intubating a lubricated orogastric tube past the esophageal hiatus where resistance most likely occurs.

If orogastric intubation is unsuccessful, percutaneous gastrocentesis at the point of maximal tympany (where the part of the stomach is gas-filled) is performed. Here, a catheter or trochar needle can be placed into the stomach to allow gas to escape. This technique can take a considerable amount of time in order to achieve gastric decompression. Heart monitoring is still important at this stage in case heart medications, such as, lidocaine need to be started. Opioids, such as, fentanyl are given with a benzodiazepine (midazolam) for pain management.

Surgical intervention is always recommended and required for hopeful prognosis. Surgery allows for proper assessment of the stomach’s health and corrects any volvulus that may have occurred. Surgery is also implemented to return the stomach and spleen back to their normal, original position and remove any dead tissue that may or may not be present. A gastropexy (anchoring the stomach wall to the right side of the abdomen) is also recommend and done at the time of surgery to prevent GDVs from reoccurring, as reoccurrence is common. Depending on the dog’s risk of pathogenic exposure during surgery, a choice between broad-spectrum antibiotics: cefoxitin sodium or cefaxolin sodium are given perioperatively.

Follow-up Care:

Some patients require recumbent hospitalized care for several days before they can be discharged. This also allows for heart, renal, and urine production to be monitored. Pain control, surgical site wound management, urinary and/or intravenous catheters, and feeding tube maintenance are also monitored during post-operative care. Animals are restricted from activity for two weeks post-surgery and low-fat smaller portioned meals are implemented to enhance gastric emptying.

Prognosis:

Many dogs recover well with a 98% survival rate, if GDV is diagnosed and treated quickly. Dogs with gastric necrosis have a survival rate of 66% and a more guarded prognosis. Poorest prognosis occurs in animals with disseminated intravascular coagulation, serious secondary infection (sepsis), heart arrhythmias, and severe damage and/or perforation of the stomach. (Mazzaferro)

References:

- Mazzaferro, Elisa M. Blackwell’s five-minute veterinary consult clinical companion. Small animal emergency and critical care 2nd edition. Hoboken: 2018 John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2018.

- Morgan, Rhea V. Gastric Dilatation-Volvulus Client handout from Iowa Veterinary Specialties. Saunders, an imprint of Elsevier Inc., 2011.

- Thompson, Mark S. Small Animal Medical Differential Diagnosis: A Book of Lists. Brevard: Elsevier Inc., 2018.

- Tilley, Larry P., Smith, Francis W.K. Blackwell’s five-minute veterinary consult: Canine and Feline 6th edition. Ames: 2016 John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2016.