Fluids, Fluids, Fluids – A case of AHDS

Written by Eliza Frentress • 2024 Scholar

Presentation

Barrett is a 7-year-old neutered male miniature schnauzer that presented to Iowa Veterinary Specialties for bloody diarrhea and vomiting. His symptoms started the previous day with pain in the abdomen. Before bringing Barrett into the ER, his owner stated that he vomited 5-6 times in the morning which were bloody, and later had an episode of diarrhea that was dark and mostly consisted of blood. Additionally, Barrett was lethargic and acting differently than his normal self.

On initial physical exam Barrett had the following measurements taken:

- Temperature: 98.2 (slight hypothermia)

- Heart Rate: 180 (slight tachycardia)

- Respiration Rate: 48 (slight tachypnea)

- Mucus Membrane/CRT: Tacky Pink/2 seconds

- Body Condition: 5/9

Diagnostics

Initial bloodwork: 7/16 4:00pm

- Glucose: 69 (artificially low due to hemoconcentration)

- Lactate: 1.4

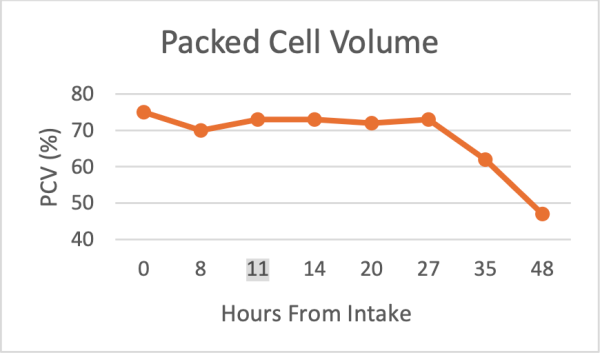

- PCV: 75%

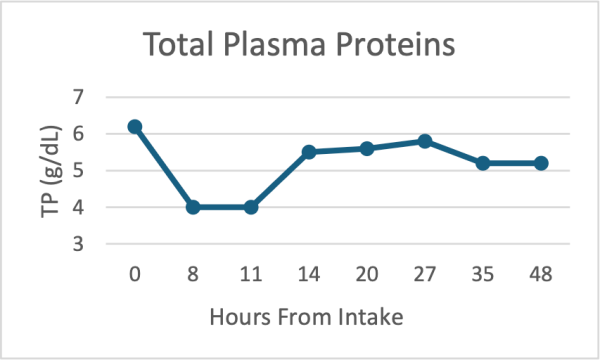

- Total Protein: 6.2

- Blood Pressure: 110

The normal range for PCV is between 37% and 55%, Barrett’s elevated PCV indicates that he had a high hemoconcentration and was severely dehydrated. Barrett had abdominal radiographs taken to rule out a foreign body or obstruction. After being reviewed by the radiologist, no evidence of a gastrointestinal obstruction was found to explain the symptoms. From these diagnostics the most likely differential was AHDS (acute hemorrhagic diarrhea syndrome). Barrett was put on fluids, anti-nausea and pain medication intravenously with the plan to recheck his blood values after starting initial treatment.

AHDS

Acute hemorrhagic diarrhea syndrome (also called HGE, hemorrhagic gastroenteritis) is a condition manifesting as stomach and intestinal inflammation and bleeding. Symptoms include very watery and bloody diarrhea along with vomiting. Symptoms normally occur suddenly and in seemingly healthy animals. Patients with AHDS can become dehydrated extremely quickly and must be treated accordingly before the dehydration and hypovolemia lead to shock. Though any dog can be diagnosed with AHDS, small breed dogs are predisposed. The exact cause of AHDS is still not known but many factors can be at play including food or microbial toxins, dietary indiscretion, stress or an overgrowth of the bacteria Clostridium perfringens, which has been found in abundance in the duodenum of dogs with AHDS (Gaschen, 2016). According to Barrett’s history he had not eaten the day prior to his symptoms or the day he was admitted to IVS, so the chance of food toxins or dietary indiscretion is unlikely. Around 80% of patients with AHDS experience vomiting around 10 hours prior to the acute hemorrhagic diarrhea, and of those cases about half contained obvious blood (Brooks, 2023). This is consistent with Barrett’s presentation.

PCV and TP are the most useful diagnostics to rule out AHDS. Patients with AHDS usually have a high PCV (greater than 65%) and normal to lowered total serum solids (including proteins, albumin, globulin, etc.) below 5.4 g/dL. Although Barrett’s TP initially fell into the normal range, his PCV was very elevated at 75%.

Bloodwork and Treatment

7/17 12:00am

Barrett’s blood was tested again, and the following measurements were taken:

- PCV: 70%

- TP: 4.0

- Potassium (K): 3.2 (hypokalemia)

- Cortisol baseline: >10

After reviewing the bloodwork, it was clear his treatment plan needed some changes. Barrett was still very dehydrated and hypovolemic with an elevated PCV even after 6 hours of fluids. Additionally, his TP had plummeted along with lowered potassium levels. Severe intestinal hemorrhage has been recorded in dogs with hypoadrenocorticism, so testing the resting cortisol levels should rule out hypoadrenocorticism as the cause of the hemorrhagic diarrhea (Busch et. al, 2022). Barrett’s cortisol levels were above the minimum threshold level of 2.0 ug/dL to diagnose hypoadrenocorticism and ruled out that cause. Treatment moving forward now focused on the hypoproteinemia and electrolyte imbalance in addition to getting the PCV lowered to a normal value.

Barrett was administered a frozen plasma transfusion in addition to his fluids to address the hypoproteinemia. Frozen plasma has fewer clotting factors than fresh frozen plasma, however since Barrett only required plasma proteins the frozen plasma was adequate. Prior to administering the plasma, Barrett was first blood typed to determine whether he would be at an increased risk for a transfusion rection. In dogs, there is one main immunogenic blood type, DEA 1.1. Barrett tested DEA 1.1 positive, and therefore was at a decreased risk for transfusion reaction. Since only plasma was used and not RBCs, the chance of a reaction was very low because the immunogenic antigen is found on the red blood cell. Most canine blood donors are DEA 1.1 negative to avoid reactions with other DEA 1.1 negative dogs. During the transfusion, Barrett’s heart rate and temperature improved and post transfusion his blood values were checked again.

Bloodwork

7/17 6:30am

- PCV: 73%

- TP: 5.5

After his transfusion, his total protein levels had risen to a more adequate level, but his PCV was still high. Although fluid therapy can take up to 7 days to fully rehydrate a patient with AHDS (Gaschen, 2016), the failure of the PCV to lower significantly since intake lead to investigating other possible diagnoses.

His current treatment included continued fluids with added KCl to restore his electrolytes, antibiotics to address any bacterial imbalances in the gastrointestinal tract, fenbendazole to target any GI parasites, and appetite stimulants. Despite treatment efforts, Barrett continued to have diarrhea and was admitted for another night.

CBC Pathologist Consult

While AHDS was still the main diagnosis for Barrett, an additional differential of polycythemia was investigated. A CBC and blood smear were sent for review by a pathologist. Polycythemia is the presence of increased RBC volume due to overproduction in the bone marrow. It can have secondary causes such as dehydration as well. Barrett’s CBC and smear were reviewed by a pathologist but due to his dehydration status and low plasma protein levels, an accurate investigation of polycythemia was not possible until rehydration occurs which can take many days to weeks with fluid therapy. It was noted that protein levels are normally tightly controlled, and any fluctuations are common with pathologies in the GI tract, and inflammation among others. Although mostly inconclusive, this consult reaffirmed the most likely cause of Barrett’s symptoms being AHDS.

Treatment remained the same moving forward with emphasis on fluid continuation with electrolytes added, as well as trying to get him to eat and further increase his protein levels. He was hospitalized overnight on the 17th and continued treatment throughout the day on the 18th. His TP and PCV values throughout his stay at IVS are graphed below.

Discharge and Prognosis

After nearly 48 hours of hospitalization on fluids and additional medications, Barrett’s PCV levels finally lowered to 62% by the early morning of the 18th and reached 47% by the afternoon, well within normal limits. His final TP value was 5.2 which, while still on the lower end, with continued eating should hopefully normalize. Additional fluid therapy and a radiograph recheck were offered but with the improvements made over the two days of hospitalization, Barrett’s owner elected to take him home.

The prognosis of dogs with AHDS is good if the symptoms are addressed, and treatment is started early in the course of the disease. Being able to notice and take appropriate action when a dog is showing signs of GI disorders can be lifesaving. In the case of AHDS, adverse outcomes can include DIC, sepsis, aspiration pneumonia and even death if treatment is delayed or not taken properly (Gaschen, 2016). In many AHDS cases the patient is sent home after a few days of fluid therapy and additional medications.

In Barrett’s follow-up, he no longer had stool issues or vomiting. While still slightly lethargic from his hospital stay, he is on the road to recovery!