Corneal Ulcers

Written by Rueben Arellano • 2025 Scholar

History

Emma is a 9-year-old, spayed female Labrador Retriever who presented to IVS for evaluation of her left eye. The owner reported that the day prior, Emma had been swimming in a nearby lake and subsequently developed redness and squinting of the left eye. By the following day (day of presentation), Emma was unable to open the eye entirely, prompting the owner to seek veterinary care.

Physical Exam Findings & Diagnostics

Emma was bright, alert, and responsive on presentation. Physical examination revealed anisocoria (unequal pupil size), conjunctival hyperemia, and blepharospasm of the left eye, as well as a miotic pupil in the right eye. Emma’s body condition score was 6/9, and her pain score was 1/4. Mentation was appropriate, and all other physical exam findings were unremarkable.

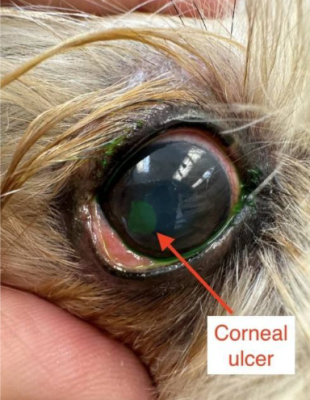

A Schirmer tear test, tonometry, and fluorescein staining were performed to assess tear production, intraocular pressure, and corneal integrity, respectively. Tear production measured 20 mm/min in the left eye (OS) and 26 mm/min in the right eye (OD), both within normal limits. Intraocular pressure was 9 mmHg OS and 15 mmHg OD, with the left eye falling on the lower end of normal. Fluorescein staining was positive in the left eye, indicating corneal ulceration.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of a Superficial Corneal Ulcer in the left eye was confirmed by Dr. Mangus based on positive fluorescein staining and clinical signs.

What are Corneal Ulcers?

The cornea of the eye is composed of four different layers: the epithelium, stroma, Descemet’s membrane, and endothelium. Corneal ulcers occur when there is sufficient damage to result in the loss of epithelium and potentially deeper layers. These ulcers are categorized based on the depth of tissue loss and fall into three categories: superficial, stromal (or deep), and descemetoceles. As stated in each name, the classification reflects how deep the injury extends into the cornea.

Superficial ulcers, involving only the epithelium, tend to heal rapidly. Epithelial repair typically begins minutes after an injury, with complete healing often achieved within 7 days. However, when the stroma is involved, healing is significantly prolonged, sometimes requiring weeks to months.

Corneal ulcers are commonly detected using a special fluorescent stain that binds to exposed stroma. If the epithelium is intact, the stain does not adhere and will rinse away. In contrast, if an ulcer is present, the stain binds to the damaged area and glows bright green under cobalt blue light. It is important to note that Descemet’s membrane repels the stain. In cases of descemetocele, this results in a characteristic ‘ring’ appearance, as the stain surrounds but does not penetrate the exposed Descemet’s membrane.

It is important to note that any corneal ulcer can become infected. Because the cornea must remain avascular and relatively acellular to maintain transparency, it has a limited immune defense. As a result, an infected ulcer should always be considered a medical emergency, as it can rapidly deepen and potentially lead to corneal rupture. Treatment typically includes topical antibiotics and close monitoring, with recheck examinations every 5–7 days.

During the ophthalmic examination, a single dose of topical atropine was administered to the left eye after the Schirmer tear test but before tonometry and fluorescein staining. Atropine is used to reduce pain and dilate the eye, but should always be used after a Schirmer tear test as it can affect tear production.

Following diagnosis, Emma was prescribed topical tobramycin (1 drop in the left eye every 8 hours for 5 days) to prevent secondary bacterial infection. Tobramycin, a broad-spectrum aminoglycoside antibiotic, was selected for its efficacy against common gram-negative bacteria.

Finally, Emma was prescribed oral carprofen (100 mg; ½ tablet twice daily until gone) to manage pain and inflammation. An Elizabethan collar was provided to prevent self-trauma. The owner was advised to schedule a recheck examination with their referring veterinarian or at IVS in 5–7 days to assess healing and ensure the ulcer had not progressed.

References

- Maggs DJ, Miller PE, Ofri R. Slatter’s Fundamentals of Veterinary Ophthalmology. 6th edition. Saunders; 2017.

- Thomasy, S. M. (2020). Practical Corneal Ulcer Management I: Superficial corneal ulcers. In Pacific Veterinary Conference 2020.

- Thomasy, S. M. (2020). Practical Corneal Ulcer Management II: Deep corneal ulcers. In Pacific Veterinary Conference 2020.

- Brooks, W. (2024). Corneal Ulcers and Erosions in Dogs and Cats. Veterinary Partner.

- Vardanyan, R., & Hruby, V. (2006). Antibiotics. In Elsevier eBooks (pp. 425–498). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-044452166-8/50032-7

- Cazayoux, J. (2013, April 25). Best Dog Breeds For Families. Pinterest. https://pin.it/6fdZ7Ly1L

- University of Tennessee. (2024). Indolent Ulcers in Dogs FAQs. In UTCVM OPHTHALMOLOGY [FAQs; Text]. https://vetmed.tennessee.edu

- Hinsperger, B. (2024, November 23). Corneal Ulcer in Dogs: In-Depth Guide to the Causes, Symptoms and Treatment | Kingsdale Animal Hospital. Kingsdale Animal Hospital. https://www.kingsdale.com/corneal-ulcer-in-dogs-in-depth-guide-to-the-causes-symptoms-and-treatment