Ethylene Glycol Toxicity in Dogs

Written by Shaine Hoffman, Iowa State University College of Veterinary Medicine?Class • 2019 Scholar

History

Max is a 3 year old, castrated male Pit Bull mix that presented to Iowa Veterinary Specialties due to loss of balance and coordination, walking in circles, and urinating while walking. He has also been trembling. Max has no prior history of seizures to the owners’ knowledge, but they have owned him for only three months. There is no known exposure to drugs, medications, toxins, compost, garbage, etc. but he is free to roam three acres of land. He is current on vaccinations.

Physical Exam

On presentation, Max was depressed but responsive, exhibited uncoordinated movement (ataxia) and muscle tremors, and was dribbling urine. His mucous membranes were tacky, indicating that he was approximately 5-7% dehydrated. His temperature, heart rate, and respiration rate were all within normal ranges, and the rest of his physical examination was unremarkable.

Diagnostic Results

Upon admittance to IVS, blood was drawn for a complete blood count (CBC) and a chemistry panel. The results of the chemistry panel were within normal limits, and the CBC showed eosinopenia (low number of eosinophils), which can be a result of stress. The remainder of the CBC was unremarkable.

A urine sample was collected for urinalysis. The specific gravity, which measures how dilute the urine is, was 1.042 (normal range = 1.016 – 1.060). The urine also was positive for glucose (50 mg/dl). Glucosuria, or glucose in the urine, can be an indicator of diabetes mellitus and other kidney deficiencies. The remainder of the urinalysis was unremarkable. An in-house urine test for drug metabolites including marijuana, amphetamines, benzodiazepine, cocaine, opiates, and barbiturates was negative.

Finally, a test for ethylene glycol, the active ingredient in automotive antifreeze, was run on blood serum and was positive at 50 mg/dl.

Diagnosis

Based on the results of the diagnostic tests, Max was diagnosed with ethylene glycol toxicity. The minimum lethal dose of undiluted ethylene glycol for dogs is 4.4 mL/kg. For a dog of Max’s weight, 30.3 kg, the lethal dose would be 133.3 mL or roughly 4 fluid ounces (Grauer). It is unknown how much ethylene glycol Max actually consumed.

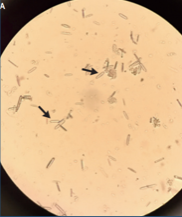

It is noteworthy that Max’s urine did not contain the monohydrate calcium oxalate crystals typical of ethylene glycol toxicity. These crystals are formed when one of the toxic metabolites of ethylene glycol, oxalic acid, binds to calcium found in the blood (Hovda).

Symptoms of ethylene glycol toxicity begin appearing almost immediately after ingestion and are similar to symptoms of alcohol intoxication. Symptoms include vomiting, increased drinking, increased urination, CNS depression, stupor, ataxia, knuckling, and other neurologic symptoms (Grauer).

Prognosis

Max’s prognosis was guarded, especially given that it was unknown how much ethylene glycol was consumed and when it occurred. The prognosis worsens as the time between ingestion and initiation of treatment increases (Grauer). The potential for acute kidney failure, as well as the possibility of permanent kidney damage, was discussed with Max’s owner.

Ethylene glycol is broken down in the body into many toxic metabolites, including oxalic acid, by an enzyme called alcohol dehydrogenase. The calcium oxalate crystals formed by oxalic acid and calcium accumulate in the kidneys and cause acute kidney injury and kidney failure (Hovda).

Treatment

There are three main goals associated with the treatment of ethylene glycol toxicity: 1) Decrease the amount of ethylene glycol that is absorbed, 2) Flush the unabsorbed ethylene glycol out of the animal’s system, and 3) Prevent absorbed ethylene glycol from being metabolized (Grauer).

An IV catheter was placed in Max’s left front leg so that IV fluids could be administered to flush out any remaining ethylene glycol. A constant rate infusion (CRI) of ethanol was also started and administered via the IV catheter. Ethanol acts as a competitive inhibitor and prevents the metabolism of ethylene glycol by alcohol dehydrogenase. However, there are some adverse side effects associated with ethanol treatment and Max needed to be closely monitored. Ethanol causes sides effects including nervous system depression/sedation, low blood glucose, low body temperature, respiratory system depression, and the risk of aspiration pneumonia (VIN).

A urinary catheter was also placed so that Max’s urine output could be closely monitored. Because ethylene glycol toxicity impacts kidney function, if the amount of urine produced isn’t in line with the amount of fluids being taken in, repeat blood tests need to be done to evaluate the kidneys. Initially, Max’s urine output was well below the amount of IV fluid he was receiving, but eventually fluid output caught up to fluid input.

A repeat chemistry panel was done 24 hours after admittance to IVS. Max’s blood urea nitrogen (BUN), an indicator of kidney function, was slightly lower than normal, but that is to be expected with the high volume of IV fluids Max had received. The remainder of the panel was unremarkable.

The treatment plan of IV fluids, ethanol CRI, and close monitoring was continued. A chemistry panel was repeated 48 hours after admittance. Max’s BUN was again just below the normal range, and everything else was again unremarkable.

Discharge

After Max’s 48 hours chemistry panel was normal, he was discharged to his owners. He still had some residual ethanol in his system and was therefore slower, more sedate, and more unsteady on his feet than normal, but his owners were advised that those side effects should wear off overnight. His owners were also advised to bring Max back to a veterinarian if they had any additional concerns, but the IVS veterinarians did not anticipate any complications.

Return Visit

Almost 24 hours after being discharged, Max again presented to IVS for shaking and drooling. His owner reported that Max urinated for a very long time a little while ago, and aside from the shaking and drooling has been normal since being discharged the night before. The shaking and drooling started after he urinated, and lasted for about 15 minutes. They have been monitoring him very closely to ensure that he doesn’t ingest anything he shouldn’t.

Everything was normal on physical exam. A urine sample was collected for urinalysis, which showed slight pyuria (white blood cells in the urine), hematuria (blood in the urine), and bacteriuria (bacteria in the urine). A blood sample was also collected for a chemistry panel and a CBC, all of which was within normal limits.

Max was diagnosed with a urinary tract infection, and sent home with oral antibiotics to be given twice daily with food.

References & Citations

- Ethanol. (30 June 2017). VIN Veterinary Drug Handbook. https://www.vin.com/ members/cms/project/defaultadv1.aspx?pId=13468&id=8425407

- Grauer, Gregory F. (2019). Overview of Ethylene Glycol Toxicity. Merck Veterinary Manual. https://www.merckvetmanual.com/toxicology/ethylene-glycol-toxicity/overview-of-ethylene-glycol-toxicity?query=ethylene%20glycol

- Hanouneh, Mohamad, and Teresa Chen. (2017). Calcium Oxalate Crystals in Ethylene Glycol Toxicity. The New England Journal of Medicine. 377(15):1467. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMicm1704369

- Hovda, Lynn, Ahna Brutlag, Robert Poppenga, Katherine Peterson. (2016). Blackwell’s Five-Minute Veterinary Consult Clinical Companion: Small Animal Toxicology. Ames, Iowa: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.